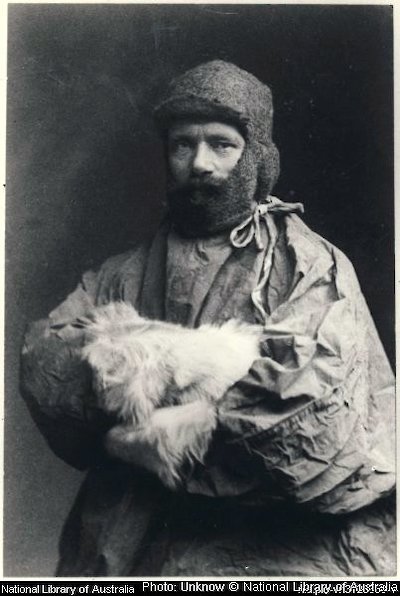

Frank Wild

AAE position: Leader of Western Party, sledge-master

In their own words

Should it ever be my lot to venture on a like expedition, I hope to have some, if not all, of the same party with me.

— Wild, in his report to Mawson on the Western Base

Born in in Skelton, North Yorkshire, in 1873, Frank Wild first went to the Antarctic with Robert Scott in 1901 — the beginning of a 20-year Antarctic career that also included working under Shackleton and Mawson, often in the toughest of circumstances. Wild turned out to be the epitome of a polar explorer — practical, hard-working, loyal, reserved, unflappable — with an incomparable record of Antarctic experience on land and sea.

Frank Wild joined the British merchant service in 1889, travelling to South Africa, Asia and Australia, until joining the Royal Navy in 1900, in which he served aboard HMS Edinburgh and HMS Vernon. The following year he joined Scott’s National Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1904, serving on an extended sledge journey that reached an altitude of 2700 metres. His experience won him selection by Ernest Shackleton to join the southern sledging party in the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907–1909, during which he ventured closer to the South Pole than anyone before.

Mawson got to know Wild during Shackleton’s expedition, and saw him as one of the two essential members of the AAE (along with ship’s master John Davis). He put Wild in charge of the ‘Western Party’, which was to explore lands four hundred miles and more to the west of Cape Denison. Wild finally set up a base at the western end of the great Shackleton Ice Shelf, in the region first visited by the 1901 German Gauss expedition. The base was built on floating ice 27 kilometres from land.

This was Wild’s first big opportunity to show his leadership ability, and he did not disappoint. Through a long winter and succeeding summer he and his six companions completed an arduous program of sledging to the east, west and south of their home on the floating ice shelf, mapping hundreds of miles of Queen Mary Land’s coast and hinterland. They completed the work without fuss or rancour; Wild said at the end he would be happy to serve with the same team again.

He returned to England in time to join Shackleton again, this time on the epic ‘voyage’ of the doomed Endurance, trapped and finally crushed by the ice of the Weddell Sea.

Having lost their ship, the men endured nearly five months on sea ice and stormy seas. Near the end of their icy journey, when it became clear his beloved sledge dogs would have to be disposed of, Wild himself took on the task of shooting them.

On finally reaching desolate Elephant Island in the South Shetlands, Shackleton decided to take five others to attempt a whaleboat journey to seek help from whalers at South Georgia. It was Wild whom he put in charge of the remaining 22 men in his expedition party. The castaways endured 138 days through winter and early spring huddled under upturned whaleboats before being rescued. But they all made it back alive.

On returning to war-torn Europe, Wild took up a naval position that took him to Spitsbergen and Russia. During this assignment he met Vera Altman, the widow of a British official in Vladivostok, whom he was later to marry.

For a few years he tried tobacco farming in southern Africa, without much success. It was easy for him to agree to Shackleton’s offer to venture once more into the Antarctic, on Shackleton’s final voyage aboard Quest in the summer of 1921–1922. When ‘the Boss’ took ill and died, Wild took over command of the expedition, but in the absence of a clear brief from his former leader he lost the will to continue.

In 1923, he returned to South Africa with Vera, trying cotton farming and railway construction. But failing finances and marriage (ending in divorce in 1928) took their toll on his health. He was to marry again, but his financial difficulties continued. He supplemented a meagre income from bar-tending (interspersed with drinking bouts) and mining by giving lectures on his Antarctic adventures.

No other explorer was awarded the Polar Medal (with four clasps) on as many occasions, but financial reward in the form of a British government civil list pension came too late to be of any benefit to Frank Wild. He died in August 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, from diabetes and pneumonia.