Studying other lives

In their own words

With the material collected by the ship during her winter program, & the collections from Macquarie Island, Western base, Adélie Land & the journey home I think we should have a record collection for any Antarctic expedition & should that happen then I will be satisfied.

— John Hunter’s diary, 5 September 1912

[I]n one fell swoop we got a biological collection … a mass of starfish, sea urchins, sponges, polyzoa, sea cucumbers, gigantic sea spindles, shells, worms, crustaceans & heaps of other things.

— Charles Laseron’s diary, 9 September 1912

In these dirty green lumps of ice are represented practically the whole of the low life which exists and actively multiplies in Antarctica: algae, diatoms, protozoa, rotifera, and bacteria.

— Archibald McLean (1918) Bacteria of ice and snow in Antarctica, Nature, September 12 1918

The temporary human residents of Cape Denison shared their domain with many other species. The obvious ones were the seals, penguins and flying birds which each summer make their home around Antarctica’s coast. Less obvious were the mites and other parasites of the larger animals, the lichens, the marine plants and animals of Boat Harbour and nearby coasts, and the bacteria that could be found on any living tissue — notably that of fellow-humans.

John Hunter and Charles Laseron had responsibility for biological collecting. In the early months the focus was on seals and birds — an activity necessarily accompanied by widespread and systematic killing of seals and penguins for winter protein for both men and dogs. Laseron (whose main prior interest had been geology) found the slaughter distasteful, but he stuck at his task. The preparation of skins was a gap-filling winter task for the two.

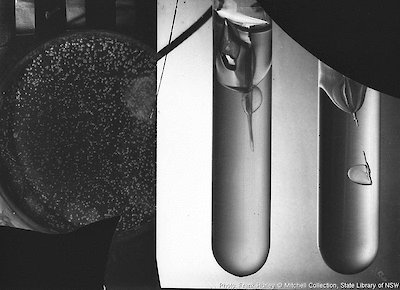

Medically-trained Hunter relished the chance to tackle the wider biological world, taking every opportunity to dredge the sea-bottom for animal and plant specimens and noting with pleasure the often-unexpected finds in the muddy deposits. But with incessant winds blowing both sea ice and the whaleboat out to sea, Hunter had to use shore-based dredges and fish traps. A discovery of a nearby lake by Frank Hurley brought forth rotifers and protozoans, which Hunter duly preserved ‘for whoever is to describe them’.

When he he was not working in general biology, Hunter studied blood samples from both Cape Denison animals and his human companions. Sharing this interest was Archie McLean, who took monthly blood and skin samples from his colleagues, earning the nickname ‘Vampire’. His studies of the impact of Antarctic life on humans took in opsonins, protein fragments which help white blood cells destroy foreign bodies.

Other scientific preoccupations of McLean included the study of bacteria (setting up bacterial cultures from swabs from killed animals), algae and protozoa. Around midwinter and again in spring he planted seeds from various Australian sources, including wheat and barley, in Cape Denison mud (noting in his diary that one wheat plant ‘grew about nine inches with several bifurcations and was yellowish-green in colour’).