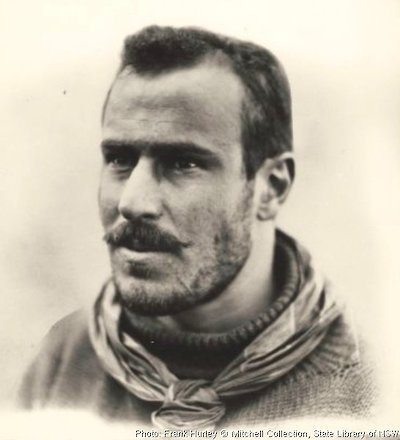

Francis Howard Bickerton

AAE position: In charge of ‘air-tractor’ sledge

In their own words

Fumbling with bulky mitts, handling hammers and spanners, and manipulating knots and bolts with bare hands, while suspended in a boatswain’s chair in the wind, the man up the mast had a difficult and miserable task. Bickerton was the hero of all such endeavours. His work was all the more remarkable because much of it was accomplished in considerable wind.

— Mawson in Home of the Blizzard, on Bickerton’s work in the erection of Cape Denison’s wireless masts.

These present conditions are nearly enough to cure a man of a desire to poke his nose into the odd corners of the earth.

— from Bickerton’s AAE diary

Francis Howard Bickerton was larger than life, packing several normal lifetimes into his 65 years. Born in Oxford, England, in 1889, Bickerton studied engineering before deciding that adventuring was more his style.

Early in 1911, Bickerton teamed up with a fellow-adventurer, Aeneas Mackintosh, who had recently returned from an Antarctic expedition with Ernest Shackleton. The pair headed off into the Pacific to hunt for Robert Louis Stephenson’s fabled ‘Treasure Island’ which Mackintosh was convinced was lonely Isla del Coco, south-west of Central America. Their plan was to pass the loot on to a pair of charitable London ladies planning to establish an orphanage, but their search came to nothing.

Immediately on his return Bickerton volunteered to serve with Mawson as electrical engineer and motor mechanic. He was assigned responsibility for maintaining the Cape Denison wireless station and the ‘air-tractor’ — the wingless Vickers aircraft used to tow sledges.

Leader of the Western Sledging Party in the 1912–13 summer, Bickerton, along with Leslie Whetter and AJ Hodgeman, made the first discovery of a meteorite in the Antarctic. Antarctica has since turned out to be a meteorite treasure-trove; the space rocks, burnt smooth and black by their fiery passage through Earth’s atmosphere, are easily spotted against the snow.

Bickerton stayed behind with five others when Mawson’s party failed to return in time for Aurora’s departure early in 1913. By this time his skills had become legendary — they covered such a wide range that his colleagues came to expect him to meet virtually any practical challenge. In Home of the Blizzard Mawson praised his culinary contribution, a popular ‘mixed-spice pudding’ (resulting from a happy accident in the preparation).

Wireless communication was important to the 1913 group, which meant the mental breakdown of the wireless operator Sydney Jeffryes was a tough blow. Bickerton willingly stepped into the breach, taking full charge of wireless operations, and in the process taught himself Morse code.

With Bickerton’s return to England in 1914, his experience with the ‘air-tractor’ came to the attention of Shackleton, who recruited him for the Endurance expedition. After assisting with the selection of a wingless aeroplane, Bickerton elected instead to fight on the Western Front, where he served with distinction as a fighter pilot. He shot down two German aircraft and was credited with helping to establish the Sopwith Camel’s capability as a night fighter.

At war’s end, the restless Bickerton attempted farming in Newfoundland, established a successful golf club in California, and spent some years on safaris in East Africa. Back in England, he had a distinguished career as an editor and screenplay writer at Shepperton Studios in England. He was a friend of the Bloomsbury author Vita Sackville-West, and was the model for the character of Leonard Anquetil in her 1930 novel, The Edwardians.

When World War II started he enlisted again, with the Royal Air Force. He died in Wales in 1954.