Panoramas and perils

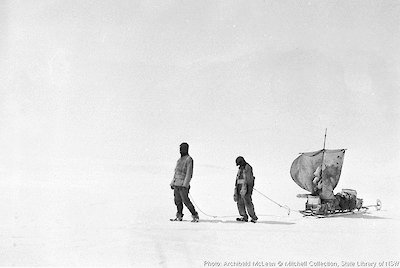

The East Coast Sledge Journey departed Cape Denison 8 November 1912; farthest point 18 December 1912; returned 16 January 1912; distance travelled c 870 km.

The task of Cecil Madigan’s Eastern Coastal Party, wrote Mawson, was ‘delineation of the coastline immediately to the east of the … Mertz Glacier Tongue’. ‘Immediately’ was translated by Madigan and his colleagues, Percy Correll and Archie McLean, to mean travelling over 400 kilometres from their home base.

Theirs was the most spectacular of all the sledging trips. Barely had they separated from Stillwell’s and Mawson’s groups when, just above the great Mertz Glacier tongue, a ‘wonderful panorama’ — the first of many — opened up before them. ‘The sea lay just below,’ wrote Madigan, ‘sweeping as a narrow gulf into the great, flat plain of debouching glacier-tongue which ebbed away north into the foggy horizon. A small ice-capped island was set like a pearl in the amethyst water.’

It was also a journey full of perils. They had noted earlier the danger of white-out conditions, which Madigan called a ‘snow-blind’ day, when

… the sky is covered with a white even pall of cloud, and sky and plateau seem as one. No shadows are cast; it is impossible to tell the nature of the surface even at one’s feet. One walks into a trench or a 3-ft. sastrugi without seeing it; the world seems one huge white void.

There was the fact that they would be forced to venture on to sea ice — easy enough to traverse when it was in one piece, but always with the risk that they would be swept out to sea in a wind-blown ‘break-out’. Here they were fortunate — the ice was so unbroken and ‘fast’ (well-connected to land) that in their first experience of it they travelled for two days without even knowing they were crossing the sea!

Then there were the steep ascents and descents, involving rock-hard, slippery ice. And the crevasses. The East Coast journey involved extensive traverses of coastal ice and two crossings each way of major glacier tongues. Nowhere could they feel safe from the threat of falling suddenly through a thin snow bridge into a blue-black void. Madigan’s description of his first crevasse experience is almost matter-of-fact, reflecting the multiple crevasse falls experienced by the party:

The colour in a crevasse is indeed beautiful, but so much depends on the point of view, the best position, in my opinion, being face-downwards … and attached to an alpine rope with several strong men at the other end … I was rather comforted in a way by my fall … as it thoroughly tested my harness. … I felt the effects … in great stiffness and soreness of the back, all day, and it took several days more before I was quite right again.

For all the difficulties — the stumbles and falls, the snow-blindness, the frostbite, the blisters and cuts and bruises — there was the constant stimulation of an ever-changing land and seascape, always something novel and unexpected ahead:

… With four weeks' provisions we made a new start to cross the Ninnis Glacier on December 3, changing course to E 30 degrees N., in great wonderment as to what lay ahead. In this new land interest never flagged. One never could foresee what the morrow would bring forth.

Scientific responsibilities were never far from their minds. Madigan and Correll attended assiduously to observing the physical environment, notably mapping and navigational duties, and McLean took charge of biological observations, for which opportunities abounded along the coast.

In granite sands at Penguin Point, between Mertz and Ninnis glacier tongues, McLean was excited at the discovery of two kinds of mite-like insects, including some eggs. Numerous bird specimens collected included petrel species not found elsewhere by the AAE.

Near the extremity of their trek, Madigan the geologist was thrilled at the discovery of sedimentary rocks at Horn Bluff (named later after WA Horn of Adelaide, an AAE patron). In some places, reported Madigan, ‘the carbonaceous matter was rich enough to form coal’.

The last part of the return journey proved the toughest part of all: persistent wind and blizzard conditions repeatedly kept them tent-bound — and, toward the end, hungry, when they were held up in reaching a vital food depot. Their arrival at Cape Denison, one day past the deadline, was truly memorable:

We tumbled in, to be assailed by a wonderful odour which brought back orchards, shops, people — a breath of civilization. In the centre of the floor was a pile of oranges surmounted by two luscious pineapples. The Ship was in!