Magnetic fortresses

In their own words

He [Webb] was conscientious to a degree, and his job was, during the winter months, very unpleasant. Day by day he had to fight his way to the magnetic hut and secure records automatically made during the previous 24 hours. Periodically he made what is termed a quick run — that is for four hours the readings would be personally noted, checked and recorded. On these occasions one of us always accompanied him as recorder. The four hours seemed interminable.

In a temperature of from 10° to 20° below zero [Fahrenheit], there was no chance of movement in the cramped space of the magnetic hut. It was impossible to write with mitts on, so the had had to be kept uncovered, and got so stiff and cold that the pencil could hardly be held. In fact a quick run meant that two individuals struggled back to the huts in a half-frozen condition.

— Charles Laseron, South with Mawson

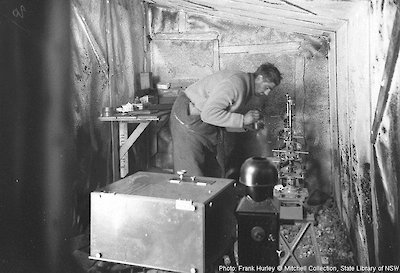

Christchurch-born Eric Webb was 22 years old when Mawson put him in charge of magnetic observations at Cape Denison, with an Australian Army junior officer from Melbourne, Robert Bage, as his assistant. With completion of the Main Hut’s outer cladding early in February 1912, their first task was to build two magnetic observatories — the ‘Magnetograph House’ and the ‘Absolute Hut’, both completed before the end of March.

To produce acceptable records, Webb’s instruments needed to be protected from buffeting by hurricane winds (requiring that the instruments be set into rock and tonnes of rock be stacked around the huts’ walls) and shielded from the magnetic influence of nearby materials, which required that non-ferrous metals be used in putting them together.

Traversing the 350 metres from the Main Hut to their workplace was the hardest part of Webb’s and Bage’s work. Blinding snow driven by relentless katabatic winds often had them feeling their way on hands and knees, even in the middle of the day — unable to see more than an arm’s length in front of their faces. They learned by heart every little detail of their route, determining their location by identifying each rocky outcrop through touch.

Their time in each hut was usually brief, during which they trimmed the lamp and changed the recorder’s photographic paper. ‘International term days’ — the first and 15th day of each month — required more detailed observations, and sometimes Webb and Bage had to spend hours at a time in the Absolute Hut to work out the standard values by which to verify the record from the Magnetograph Hut.