Adventures on the sea ice

In their own words

Poor brutes [the dogs] they have had a bad time these last 2 weeks — 13 days of continuous wind, storm & drift! And this the middle of Spring, with apple trees all in bloom in Tasmania.

— Harrisson’s diary, 22 October 1912

‘The wind bloweth where it listeth’ — and how it has listeth for the last 15 days. All night, all today, the same steady strong breeze, the same laboured roaring, the same flap and roll of the tent the same stinging, rain-like spray-like, drift, that you can see, through the thin worn tent sides, as waves of smoke parting on either side and flying past.

— Harrisson’s diary, 24 October 1912

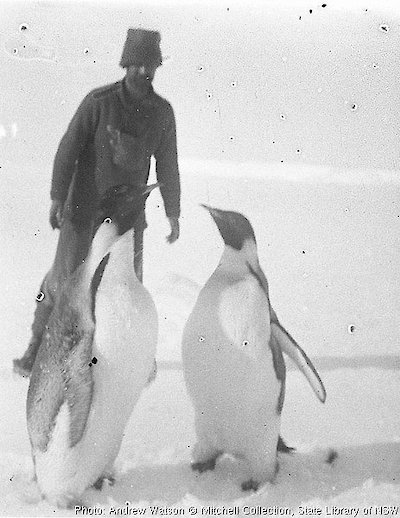

Jones, Hoadley and Dovers formed the main depot-laying party for the coming Western Sledge Journey, with support from Moyes and Harrisson. Departing on 26 September, only 12 kilometres out the group found themselves tent-bound by a heavy snowfall, during which the dogs, already well-fed, took it upon themselves to slaughter five helpless emperor penguins.

Harrisson, the biologist, did not disguise his distress: ‘such beautiful birds,’ he wrote, ‘such a yellow shade on their breasts, that seemed to change and deepen with every movement, and all blood-smeared and torn.’ Next day the men had the satisfaction of whipping the dogs off another curious emperor, who on their departure ‘stood there dejectedly … [and] appeared deeply disappointed in us.’

As they approached a glacier to the west, Harrisson noted that the sea ice seemed newly-formed, indicating that it had re-formed since they had landed nearby the previous summer. Reaching the glacier, they crossed many crevasses to reach a high point, only to find a deep chasm and broken ice barring progress further westward.

Jones resolved to return to Junction Corner, at the point where Shackleton Ice Shelf met Antarctic continental ice, to attempt an ascent from the sea-ice on to the ice sheet. Finding a ramp, they marched on to solid, crevasse-free ice sloping up to around 300metres above sea level.

But the weather was not finished with them. A strong wind opened seams in one of the tents, so — as for the eastern journey a month earlier — the men let it down and used it as a roof over a trench in the ice.

They remained in their shallow, icy trench for 15 days, during which they laid down a food depot. The brief published report would have done little justice to the degree of discomfort and frustration experienced by the men: ‘They soon became heartily sick of inaction, and spent an altogether uncomfortable time. The dogs also suffered much.’

Well overdue, 13 kilometres out from the Grottoes they fell in with Wild and Kennedy, who had set out to search for them. They staggered on back to the hut, where, as Harrisson recorded, ‘five dead-tired, footsore men, crawled into bed at midnight after doing just on 28 miles’.