Frustration upon frustration

On the morning of 18 November, Wild decided to keep on a northerly course to try to find a more comfortable path across Denman Glacier. At midday he went ahead to a high point, to discover ‘the most magnificent piece of ice scenery that I have ever seen … the wildest, maddest, and yet most beautiful sight imaginable.’

And seemingly impassable. They returned to David Island, where Wild, Watson and Kennedy climbed to its highest point to get a view over the glacier, only to have the weather close in, hiding their view. Four days later they managed to get a view, but it was anything but encouraging:

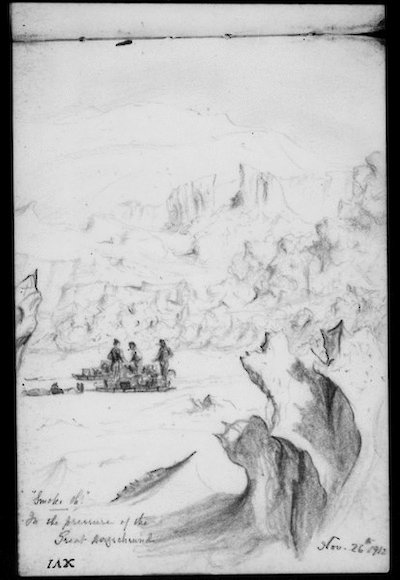

From the top of the Bluff the great stream of shattered ice of the Denman Glacier could be seen descending from the sky line about 3000 feet [over 900metres] above sea level in the south and continuing unbroken to the northern horizon. On the very sky line in the north-east great pressure blocks with cliff faces were standing up in jagged array. Beyond, to the eastward of the main shatter zone, the shelf ice was seen to be heaved in great billows.

Wild was determined not to let the glacier beat him. They tried a route that looked promising, but found the going impossibly slow. Some crevasses took an hour or two to cross. The weather turned warm, melt-water only adding to the party’s problems. After three days Wild gave up. It took 11 days to get back to David Island, where they dined on snow petrel eggs.

They headed south over the shelf ice to try a glacier crossing higher up, from the vantage of the continental ice sheet. After crossing a small branch glacier and climbing higher up the ice slopes, they saw ahead of them a rocky mountain, about 1300 metres high, which was named Barr Smith, after an Adelaide benefactor of the expedition.

And to their left, out across the chaos of Denman Glacier, they saw a second glacier (named by Mawson after Robert Scott) and what they thought was an island, which Mawson named Hordern Island, after a Sydney benefactor. It is now known as Cape Hordern — the northwestern extremity of the Bunger Hills.

Barr Smith was their turning point. Returning to David Island proved tougher than expected, over soft snow in heavy snowfalls. En route they celebrated Christmas with plum pudding, after which Wild raised the Union Jack and took possession of the land for the British Empire, sealing in a bottle a slip of paper advising of the occasion and leaving it in a rocky crevice. ‘We all cheered’, wrote Harrisson. ‘Looking round upon the desolate Ice-Cap I remarked, “We have set the bounds of Empire wider and much good may it do her!”’

From there it was a matter of a three-day trek to David Island, traversing its northern slopes before another trek over the shelf ice to the food cache left near Delay Point. Then steadily homeward via Cape Dovers and Gillies Nunataks [Islands] (named after FJ Gillies, Aurora’s chief engineer), where Harrisson found, among granite boulders, ‘great quantities of moss, large patches yards square… thick, green, spongy’.

And home, ending a journey of 490 kilometres. Anxious about Moyes, when they came near to the Grottoes they struck up a ‘marching chorus’. ‘O how relieved I felt when I saw Morton rush round the corner of the Hut, bareheaded; waved his hand to us — then, seeing there were four of us in the team, stood on his head for joy!’

He was amongst us in another minute or two, shaking hands all round. ‘Oh, you renegade!’ shaking his head at me and wringing my hand, ‘You, renegade!’, and his feelings almost overcame him.