Signals from the South

In their own words

The application of wireless telegraphy in connection with shipping was, at that time, … still in its infancy in relation to subsequent developments … To transmit from Antarctica to Australia was considered too great a distance for an installation of the power that we could reasonably include in our equipment … I decided to increase our proposed operations by installing a party at Macquarie Island with wireless equipment , which could relay to Australia messages received from our Antarctic Main Base station.

— Mawson, AAE Scientific Report, Series A, Vol 1, Part 1

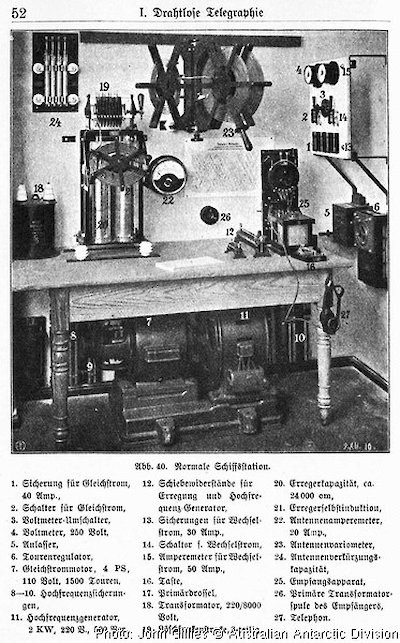

Two complete sets of Telefunken wireless apparatus were purchased from the Australasian Wireless Company. The motors and dynamos were got from Buzzacott, Sydney, and the masts were built by Saxton and Binns, Sydney.

— Douglas Mawson, The Home of the Blizzard

Though the first wireless transmissions date back to 1878, intercontinental wireless telegraphy was less than a decade old when Mawson decided to try it out in Antarctica. He decided to set up a wireless-telegraph relay station at Macquarie Island to ensure uninterrupted communication between his Australian base at Hobart and his planned three (as it turned out, two) bases on the Antarctic coast.

Mawson knew that successful transmissions to and from Antarctica would set an important precedent, removing some of the uncertainty inherent in Antarctic exploration. For the first time an Antarctic expedition would be able to announce itself — its successes and its difficulties — to the wider world.

The equipment did not come cheap. In October 1911 Mawson purchased from the Australian Wireless Company, on a buy back agreement, two 2-kilowatt long-wave Telefunken wireless sets, costing £650 each (over $65,000 in today’s dollars).

Despite its cost and relatively high power (about one kilowatt), the AAE’s wireless had a limited range, hence the need for the Macquarie Island station. This also meant that the main Cape Denison base could not communicate with Frank Wild’s Western Party, 2000 kilometres to the west.

There was no voice transmission — all radio communications used morse code telegraphy transmitting short messages both official (such as weather information) and private. The equipment operated in very low frequency (VLF) bands — about 100 kilohertz in today’s terminology.

Aerials required four Oregon pine main masts — two for Macquarie Island and two for the main Antarctic base — each of which could be broken into sections. Despite this their size and weight made them a considerable obstacle on Aurora’s already cramped decks.