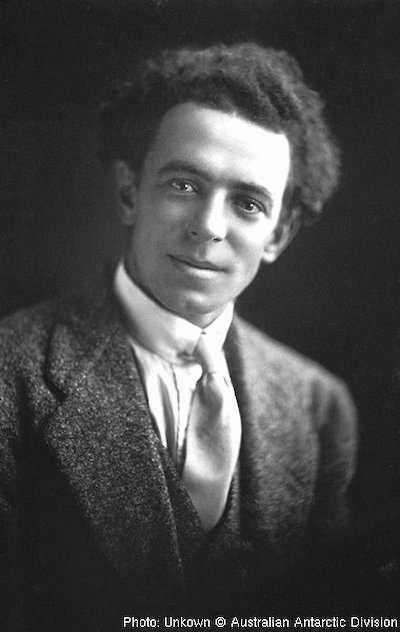

James Francis (Frank) Hurley

AAE position: Photographer

In their own words

The life and soul of our party, he exhaled humour at every pore, possessing a large fund of inoffensive wit and a weakness for practical joking from which no one of us, his 17 companions, wholly succeeded in escaping.

— From diary of Archibald McLean, 1 March 1912

James Francis (Frank) Hurley, born in Sydney in 1885, took to the new photographic technology from a young age. When he was 20 he and a colleague started a postcard business which brought him a reputation for technical excellence and taking risks to get the spectacular shot. In 1910 he staged a public exhibition of his work.

Hurley leaped at the chance to travel to Antarctica with Mawson, promoting himself with an enthusiasm not shared by his mother, who tried to persuade Mawson to reject him on health grounds. Travelling south on Aurora, Hurley’s shipmates were often astonished to see him high up in the rigging, or out on the bowsprit, seeking always the most startling and original perspective.

He never tired of photographing the many forms and moods of the Antarctic landscape. At Cape Denison and on the Antarctic plateau he obtained high-quality photographic and cinematographic records of the AAE’s many activities, including the arduous Southern Sledging Party’s journey deep into Antarctica to locate the South Magnetic Pole. His image of the figures of Whetter and Close desperately battling the hurricane-force winds of Cape Denison has become an Antarctic classic.

The AAE made Hurley an international figure as a photographer. But the adventure that was to cement his place in photographic history for all time began in 1914, when he joined Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

When the expedition’s ship, Endurance, was trapped and squeezed by ice, Hurley assiduously recorded the men’s daily lives, and captured some of the most memorable Antarctic images of all time — notably the final moments of the doomed ship before it sank from sight. To save these images, he even dived into his water-filled darkroom as the ship was sinking to rescue his negatives, and forcefully argued with Shackleton to retain a representative sample of them when weight considerations demanded they all be jettisoned. His film of the expedition, In The Grip of The Polar Pack Ice, was an outstanding financial success.

In 1917, the Australian Imperial Force took Captain Frank Hurley into its ranks as Australia’s second official First World War photographer. He went about recording battles and military life in Flanders and Palestine, arguing with his colleague, war historian CEW Bean, that composite images made from several negatives were justified in getting across the real story about war.

The war’s end saw him in action back in Australia, filming his country from the air during the final stages of Ross Smith’s 1919 flight from England. He subsequently made numerous films in Australia, North America and England. For a time he was a studio cameraman in England.

By the end of 1930 he was back in Antarctica, once more with Mawson but this time in the ship-based British Australian and New Zealand Expedition (BANZARE), investigating the landforms and marine life of the Antarctic coast and Southern Ocean. As usual Hurley was in the thick of the action, recording such events as flag-raising on Scullin Monolith and Possession Island, and the iconic portrait of Mawson in his cabin aboard Discovery. He also made a film of the BANZARE adventure, Southward Ho.

With the outbreak of World War II, Hurley was given the rank of acting Major to serve as a photographer and cinematographer, gaining an OBE for his work. His 1948 book Shackleton’s Argonauts was another successful publishing venture, followed from the early 1950s by commercial picture postcards and calendars, mostly depicting Australian scenes.

Hurley died in 1962, aged 76.