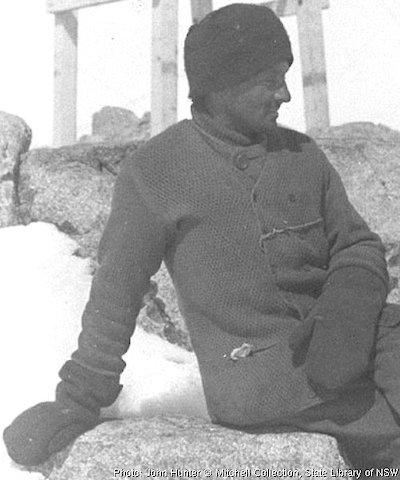

Herbert Dyce Murphy

AAE position: In charge of expedition stores

In their own words

[Murphy tells of] hair-raising scandals, with lurid details of complicated domestic situations with ludicrous climaxes … His stories have a curious suggestion of truth; they are convincing and at the same time too impossible to be true.

— Diary entry by CF Laseron, recounted in South with Mawson.

The life of Herbert Dyce Murphy, even more that of Bickerton, seems too large to be true. His fellow Antarctic expeditioners may have doubted some of the stories he told about himself, but there can be no question that his was a truly extraordinary life.

Murphy’s Melbourne family were wealthy landowners with extensive Australian pastoral interests. Born in 1879, as a boy he travelled to Russia with his mother and went to a private school in Kent, England, where his well-to-do family had extensive connections. His uncle took him as a schoolboy on three Arctic voyages, and he later travelled to Australia as a crew-member of a trading barque.

Murphy lost his family’s financial support when he refused to participate in running its pastoral interests. He passed entry examinations to study history at Oxford University, and although he claimed to have completed his studies, there is no record of any later academic success. He also claimed that during vacations he served as navigator aboard an Arctic whaler, transported reindeer across the Arctic and visited the USA.

There followed a remarkable career as a traveller and adventurer — of which Mawson’s AAE is just a part. Having been seen performing a female stage role at Oxford, Murphy was recruited by British intelligence to travel as a woman through France and Belgium to study their railways. During this time he met the Australian expatriate artist Phillips Fox, and claimed to have been the attractive woman with white parasol in Fox’s painting The Arbour.

While Murphy enjoyed his female impersonation, a deepening voice and growing hands made it difficult for him to maintain the pretence. Tutoring a whaleman’s daughter aboard a New Bedford whaler, jumping ship in New Zealand, a stint as a whale ship owner, adopting two orphan girls, and surviving Arctic besetment in ice by eating lemmings are some of Murphy’s tales from his late twenties.

Murphy volunteered for Shackleton’s 1907 British Antarctic Expedition, but was turned down on the grounds that he was effeminate, which he strongly denied. Mawson had no such qualms; he saw Murphy as a capable leader and even planned that he take charge of a third Antarctic mainland base. But with the decision to amalgamate two into the Cape Denison base, Murphy was given charge of the base’s stores.

During the 1912 summer Murphy led the supporting party (the others were Hunter and Laseron) for the exploratory sledging expedition to the South Magnetic Pole undertaken by Bage, Webb and Hurley. They were required to lay down stores for Bage’s party to enable it to travel lighter and faster for its long trek — a task which they completed to everyone’s satisfaction.

On his return to civilisation Murphy went to England, spending a year in military intelligence. He returned to Australia in 1916 to enlist with the AIF, but failed to pass an eyesight test and was discharged.

After unsuccessfully trying sheep farming, Murphy bought a property at Mount Martha on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, opening his home up to underprivileged children. He ran holiday activities and amused the children at night with stories of his many adventures. Murphy had no children of his own, though he later married at the age of 44.

He continued his association with Antarctica, spending three months each year as ice-master on Norwegian sailing ships from the early 1920s until 1965, when his employers were astonished to discover he was 85.

Murphy died at the age of 91 in 1971. A biography by Moira Watson, The Spy Who Loved Children — the enigma of Herbert Dyce Murphy, was published in 1997