Pulling power

No group leaving the close confines of Cape Denison could expect to find food or shelter along the route of their march — least of all those heading inland, away from the coast and without any prospect of slaughtering a seal or penguin in an emergency. Their sledge loads needed to include all the food and shelter they were likely to need along the way. The longer the distance and the greater the time, the more intricate and exacting the planning.

There were ways of lessening this burden. Preparation for the big sledging expeditions that started out in the late spring of 1912 included preliminary excursions on to the ice cap to establish a safe, crevasse-free route to higher ground and to lay down food depots for returning parties facing a shortage of supplies.

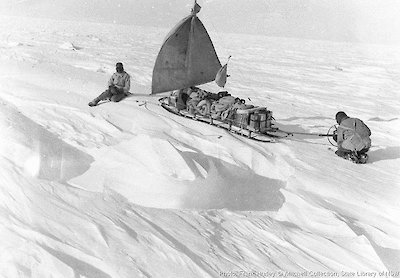

But the longer-distance journeys inevitably meant pulling a heavy load. (See the list of items, with weights, taken on the Far Eastern Sledging journey by Mawson, Ninnis and Mertz [PDF]. Most of these items were also taken by other sledging parties. © Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum). The supplies, equipment and sledges for the three-man ‘Far Eastern’ party led by Mawson weighed more than 800 kilograms — a considerable burden for a journey expected to cover about 1000 kilometres. Mawson was able to call on the help of dog teams, but others for the most part had only their own bodies to do the hauling.

The dog teams were the responsibility of two unlikely comrades, a Swiss lawyer and expert skier named Xavier Mertz, at 28 one of the party’s veterans, and Englishman Belgrave Ninnis, a 23-year-old lieutenant of the Royal Fusiliers and son of a former Arctic explorer. Sharing a love for the animals in their charge, the two men formed a close friendship over the winter months at Cape Denison.

Besides dog teams, there was a second alternative to ‘man-hauling’. The Vickers monoplane which had hit the ground at the Adelaide racecourse the previous year was part of Aurora’s cargo, minus its broken wings. Frank Bickerton had the winter task of turning it into a sledge hauler — an ‘air tractor’ — and taking charge of it on the ice, where it was to pull heavy loads up on to the plateau and, hopefully, farther afield.