Unloading - and a warning

In their own words

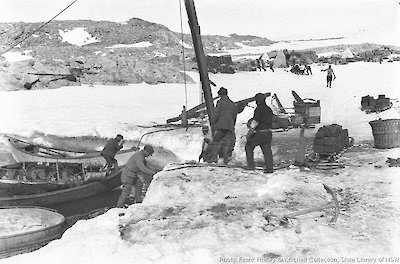

… a matter of congratulations really, that the landing has passed off so well! On some days, rough & dangerous work. Boats tossing wildly — boxes and briquettes flying down a plank that was working with the motion of the boat — One of us catching them & breaking the force of their fall, 2 stowing — & it was ‘look out’ for heads & legs, mates & boats! Really a mercy there was no mishaps; a boat would be loaded in less than ¼ of an hour — so 1½ tons of boxes of briquettes had to come down in quick succession! — & hard work in the boats while it lasted.

— Charles Harrisson diary, 17 January 1912

The perfect day of 9 January turned into a less-than-perfect evening. A chill land breeze sprang up, making the launch’s shoreward progress difficult. ‘By the time we had reached the head of the harbour, Hoadley had several fingers frost-bitten and all were feeling the cold, for we were wearing light garments in anticipation of fine weather,’ wrote Mawson:

No time was lost in landing the cargo, and, with a rising blizzard at our backs, we drove out to meet the Aurora. On reaching the ship a small gale was blowing and our boats were taken in tow.

In the rising winds, mooring the ship amongst uncharted shoals proved a much harder task than expected, with ‘depths jumping from five to thirty fathoms in the ship’s length’. Then the motor launch broke away in metre-high seas and drifted toward a wave-swept island. It was brought under control in the nick of time through some quick work by Frank Bickerton, John Hunter and Leslie Whetter.

There was a lessening of the wind’s strength the next day, and unloading resumed apace. ‘From now until the 19th there was no time to consider anything except the urgent need to get all our goods ashore while the weather held,’ wrote Charles Laseron. Working eight-hours-on, eight-hours-off shifts, the men slung or slid cargo from ship to boat, took it ashore and hauled it the 100 metres or so to the site of the hut. There was a warning in the weather, as Laseron noted:

Even during this time there were several more intervals in which gales, which we were already learning to accept as a regular feature of this region, descended upon us from the south.

The high seas made the unloading all the more hazardous. Rafts made up of construction timbers or wireless masts were put together on the water, but the winds and seas caused the occasional capsize, dunking some of the sailors in the freezing water. A derrick made by Frank Wild using wireless mast timbers allowed for easier unloading at the shoreline.

There came the time to part. On 19 January, anxious about the fast-vanishing summer and still needing to deploy the Western Party 650 kilometres or more to the west, Davis hosted the shore parties in his ward-room. With the help of ‘excellent Madeira’, the men toasted the AAE and its celebrated predecessors in the region, Dumont d’Urville and Wilkes, before clambering into a whaleboat and shouting goodbye. As the ship disappeared, Mawson’s men ‘set to work to carve out a home’.

‘The parting was a very matter of fact one,’ wrote Davis in his diary. ‘No one seemed quite to realise that we were really off. I hope that they will have good luck. They are a fine party of men but the country is a terrible one to spend a year in.’

Unloading stores and equipment

Excerpt from Antarctic Pioneers (1962). Narration and cinematography by Frank Hurley. © Australian Antarctic Division

Unloading stores and equipment

Video transcript

Frank Hurley: As the weather was delightfully calm, no time was lost in lightering ashore hut timbers, stores and equipment.

[end transcript]

Landing equipment at Cape Denison

Note the Vickers REP Aircraft in a packing case. Cinematography by Frank Hurley. © Australian Antarctic Division

Landing equipment at Cape Denison

Video transcript

Frank Hurley: It was to be our main shore base, from where sledging parties would go out east and west and south to carry on scientific work and explore the unknown.

[end transcript]