Bedding down the main hut

With Mawson at Cape Denison were Edward Bage (astronomer, assistant magnetician, recorder of tides), Cecil Madigan (meteorologist), Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz (in charge of sledge dogs), Archibald McLean (chief medical officer, bacteriologist), Frank Bickerton (in charge of ‘air-tractor’ sledge-hauler), Alfred Hodgeman (cartographer, sketch artist), Frank Hurley (photographer), Eric Webb (chief magnetician), Percy Correll (mechanic, assistant physicist), John Hunter (biologist), Charles Laseron (taxidermist, biological collector), Frank Stillwell (geologist), Herbert Murphy (in charge of expedition stores), Walter Hannam (wireless operator, mechanic), John Close (Assistant collector) and Leslie H Whetter (surgeon).

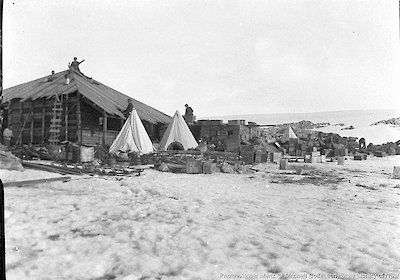

During the unloading, the first consideration had been shelter for the men. Stacked wooden cases that had been emptied of their cans of motor fuel (benzine) became walls — it quickly became known as the Benzine Hut — and sections of the case that had made the engine for the wingless aeroplane formed the roof. This accommodated most of the shore party, while the remainder lived in tents. Sleeping was no problem, as Laseron recalled:

We slept in sleeping bags of reindeer skin with the hair inside, and after a working day of some 16 hours, did not need rocking.

Now, with the final selection of the site, the ground was made ready with the help of some dynamite (and penguin guano in place of earth for tamping around the charges), and the construction began. ‘As we were securely isolated from trade-union regulations,’ noted Mawson wryly, ‘our hours of labour ranged from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m.’ Time was of the essence; prefabricating the huts in Australia and numbering parts to facilitate putting them together turned out to be a big time-saver.

Stumps for the foundations were in place by 21 January. Cement had been tried, noted Mawson, ‘but it is doubtful if any good came of it, for the low temperature did not encourage it to set properly.’ But by the end of the day — two days after the ship’s departure, the base structure had been bolted to the stumps.

Next day came the floor joists and wall frames. At the same time, the gap beneath the floors was filled with boulders gathered from round about, much as the Adélie penguins gathered stones for their nests. At the end of construction about 50 tonnes of rock had been used in the foundations.

Five days after the ship left the floor, walls and roof frame were in position. The roof work was always difficult, sometimes torture: ‘there was rarely an hour free from a cold breeze,’ noted Mawson, ‘and to sit with exposed fingers handling hammer and nails was not an enviable job.’