Keeping boredom at bay

In their own words

If you’re snowed-up in a blizzard in a sludgy sloppy tent,

And for days the drift has threshed and swished, and conversation-spent

You hazard another ‘chestnut’ on your mild forbearing mates,

And the scornful lips of someone with a wan smile oscillates.

That’s a detail, to the moment when you find your cast-iron mits,

And, having thawed them gently, find they’re going fast to bits.— From ‘When Your Mits Begin to Go’, June 1913 issue of The Adélie Blizzard

As the year wore on, the tedium of life for the AAE men was relieved only by the thought that the ship’s arrival was getting ever closer. By 20 November 1913, Archie McLean recorded in his diary this exchange of wireless messages between Frank Bickerton at Cape Denison and Charles Sandell on Macquarie Island:

Bickerton: This place is awful. Sandell: So is this — Hell!

The morale of the group was a constant concern of McLean, who as medical officer had to manage Mawson’s recuperation from a state of near-death, and, later in the year, took responsibility for the care of Jeffryes in his fragile mental state.

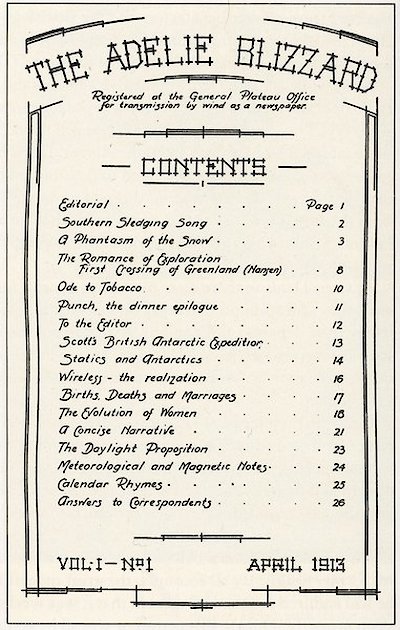

But it was through his other great love, literature, that McLean made his most enduring contribution to the AAE. When he returned he was to play a major part in the publication of the scientific reports, but in 1913 at Cape Denison the need to maintain morale presented a much more pressing problem. His solution was the Adélie Blizzard.

McLean had an enthusiastic supporter in Mawson, who had been a significant contributor to that other great literary relic of Antarctic exploration, Ernest Shackleton’s Aurora Australis. The Blizzard, however, had one great advantage over its predecessor — when the wireless was working it had access to cable news from around the world.

McLean’s work began early in April and continued for seven monthly issues, recording the vicissitudes (with the exception of the mental breakdown of Jeffryes) of life at Cape Denison. Mawson recalled:

contributions were invited from all on every subject but the wind. Anything from light doggerel to heavy blank verse was welcomed, and original articles, letters to the Editor, plays, reviews on books and serial stories were accepted within the limits of our supply of foolscap paper and type-writer ribbons.

McLean’s sense of the need to maintain good spirits is evident in a diary entry on 10 August, at a time when morale was at its lowest ebb, with winter still upon the group and Jeffryes behaving ever more erratically. McLean wrote in his diary of a sense of shame at complaining when they looked at ‘the awful privations of the old Arctic explorers’ — ‘We have splendid food, a comfortable hut and almost everything we need’.

His added remark is telling. They had all they needed except ‘the convenience of civilisation, the society of those we love best, good music (for my part), the association with others of our own calling or profession, the mass of human beings whom we find out, now, we love just for their humanity’. The yearning behind his words is unmistakable.